By Ronae Watson

The race-based social concepts of American society generally involve two groups: the “superiors” and the “inferiors.” The superiors are usually assumed to be white, which leaves people of color in the inferior sub-genre of the racial hierarchy. Huey Newton and James Baldwin wrote during a time when inferiority and incapacity were threaded throughout the entire experience of Black individuals. These baseless ideas about race made their way into the education system and caused Black students to be immediately presumed incompetent. The assumption that Black students were inherently less academically capable in comparison to their white counterparts eventually caused them to feel trapped in an endless cycle of racial discrimination. To prevent Black Americans from falling victim to this cycle, Newton and Baldwin proposed that both the “inferiors” and “superiors” have to realize that they have been disillusioned by the racial ideas they’ve come to accept as reality.

James Baldwin discusses how both racial groups operate in a society tainted with double disillusionment, but he zeros in on the disillusionment of the “superiors.” James Baldwin writes, “But a black child, looking at the world around him, though he cannot know what to quite make out of it, is aware that there is a reason why his mother works so hard, why his father is always on edge…” and “...in fact it begins when he is in school—before he discovers the shape of his oppression” (Baldwin, 1998, p. 680). This passage highlights how school contributes to the uniquely racialized experience of Black Americans. Being labeled as “inferior” in a racialized society does not allow you to be oblivious to your oppression, and Baldwin argues that all Black Americans have some level of awareness regarding the prejudice and discrimination that govern their lives. Baldwin contrasts the early awareness of Black Americans with white Americans by claiming that, “…some [white children will] near forty [will] have never grown up, and …will never grow up, because they have no sense of their own identity” (Baldwin, 1998, p. 683). This shows that growing up in a position of presumed superiority discourages white Americans from observing the racial societal structures present because they are beneficial to them.

Having a white American's sense of self and identity being founded on baseless claims is not a one-off thing. The disillusionment of white Americans is not impersonal and is rather dangerous because their obliviousness is a contributing factor to America’s racialized machine. Baldwin reveals his solution to this issue when he writes, “If, for example, one managed to change the curriculum in all the schools so that Negroes learned more about themselves and their real contributions to this culture, you would be liberating not only Negroes, you'd be liberating white people who know nothing about their own history (Baldwin, 1998, p. 683). This quote directly addresses the American education system’s tendency to incorporate ideas in its curriculum that continue to perpetuate disillusionment. Baldwin proposes that changing the narrative of education to reflect the true historical circumstances of race in this country is a two-way street. Black Americans would benefit from this change because the shape of their oppression can take a new form that does not portray their history as one of just suffering, but also of resilience. For white Americans, this change would serve as a well-needed wake-up call that will result in a strengthened sense of self that is not based on falsehoods.

Huey Newton’s writing is filled with instances where Baldwin’s restorative approach to the educational system would have benefited his adolescent development. Newton describes his school experience as, “…a socio-economic and racial warfare being waged on battleground of our schools, with… middle-class teachers provided with a powerful arsenal of half-truths, prejudices, and rationalizations, arrayed against hopelessly outclassed working class youngsters” (Newton, 2009, p. 17). This passage provides insight into what day-to-day life in a heavily racialized school system would feel like. Newton reports that it felt like his teachers were waiting for him to do the wrong thing, even when he was following the school’s program (Newton, 2009, p. 20). He reveals that it was not uncommon for his white educators to lower their academic standards for Black students or disproportionately subject them to harsh disciplinary measures. Learning in an environment where Black students are seen as inferior, are not expected to succeed, and are presumed to be incompetent only helps to condition Black students to fall victim to America’s racial cycle. Black Americans were taught to believe that they were inadequate learners compared to their white counterparts, just to be ridiculed when they exhibited the expected inadequacy they were conditioned to have. Being blamed for falling victim to the prejudices society placed on the Black individual showcases how the false racial structure that America operated upon manifested itself in the education system.

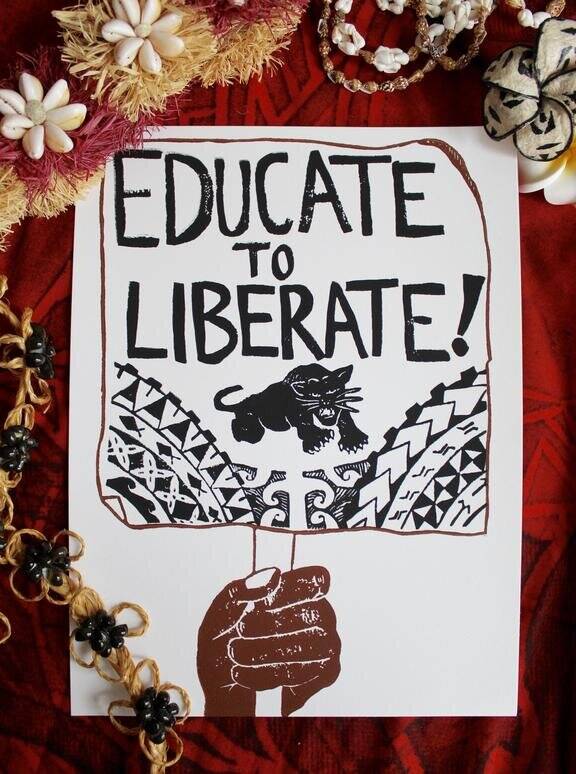

Since Black students are conditioned into believing they cannot succeed, Newton proposes surrounding them with Black people who have managed to succeed against all odds will counteract this harmful way of thinking. The benefits of having a role model are made clear when Newton writes that, “[he] always admired Melvin’s intellectual abilities; it was he who helped me overcome my reading difficulties” (Newton, 2009, p. 32). This quote reveals how having a positive figure, like Melvin, in Newton’s life led to positive changes. Seeing Melvin as a Black intellectual made education and learning seem more attainable for Newton. Once Newton began to learn, he never stopped, and this is because he also had intellectual capabilities, but never had anyone to help him unlock his potential. Newton also writes, “We, too, were in prison and needed to be liberated to distinguish between truth and the falsehoods imposed on us” (Newton, 2009, p. 77). This passage most directly recognizes how daunting America’s racial education system and society can feel because Black individuals are placed in situations where it may feel as if all odds are working against them. However, Newton recognizes America’s racial limitations as anything but the truth. For him, the solution to America’s racial problem is for young Black Americans to be provided with positive reinforcement outside of the classroom that will help guide them through the myths, truths, and struggles that surround the Black experience.

Newton and Baldwin agree that the social construct of race clouds the importance of the Black experience, and that education is a tool that can be used to empower Black people. However, since education has been mishandled and morphed into a tool to aid Black oppression, America’s education system needs to undergo a revamp to make sure it is favorable to all its recipients. James Baldwin believes the revamping lies within course material that accurately covers history. In doing so, Black and white Americans will be reeducated and racial myths will no longer govern them. Newton believes that it is important to have a figure outside of the classroom that lets Black students know that the metrics of their success do not have to be defined by their race.

Works Cited

Baldwin, J. (1998). Collected essays. Library of America.

Newton, H. P. & Blake, J. H. (2009). Revolutionary Suicide. Penguin Books.

Add comment

Comments